Andre Watson Shares What's Missing from the Gene Editing Industry — And how to Block the Coronavirus

CMN Intelligence - The World’s Most Comprehensive Intelligence Platform for CRISPR-Genomic Medicine and Gene-Editing Clinical Development

Providing market intelligence, data infrastructure, analytics, and reporting services for the global gene-editing sector. Read more...

Years ago, Andre Watson, co-founder and CEO of Ligandal, started to develop a standardized delivery tool that could bring gene-editing machinery to any cell in the body.

After graduating college in 2013, Watson started Ligandal to fill in what he sees as a crucial gap in the genetics industry: Scientists are finding more and more ways to treat disease or improve the human condition with CRISPR and other gene-editing tools, but there's no standardized platform or tool to get the gene-editing machinery where it needs to go within the body.

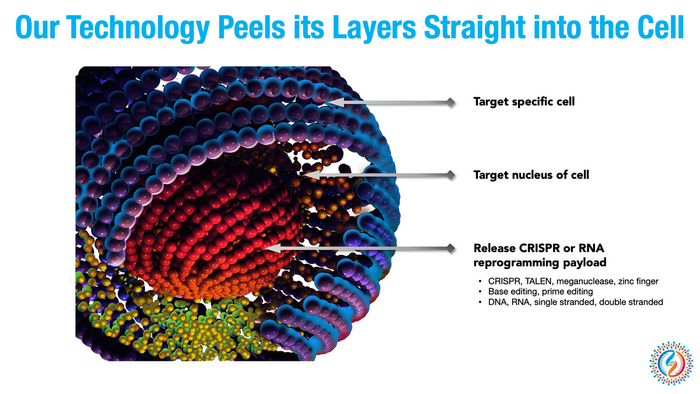

»We want to have the underlying technology in place to be able to direct to these payloads, like CRISPR, to any cellular address,« Watson says.

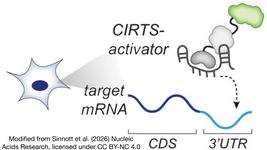

The company was making steady progress. Watson and his team developed synthetic peptides capable of targeting receptors on specific cell types, allowing them to shuttle gene-editing machinery to the exact organ or intended cellular target rather than merely injecting them and hoping it all worked out.

»We want to have a set of platforms for targeting all these different tissues that can be rapidly tailored,« Watson says.

Pivot to make SARS-COV-2 antidote

The company had shown impressive results in targeting T cells and the haematopoietic stem cells that act as progenitors to blood cells and much of the immune system, with plans to expand to other cell types. But then, just as it disrupted every other aspect of life, the coronavirus pandemic came in and took its toll — and Watson rapidly switched gears to help out.

In early August, Ligandal published a preprint paper describing SARS-BLOCK: an adaptation of the company's targeted delivery system that, instead of carrying molecules to a certain cell, binds to the ACE2 receptors favoured by the coronavirus to bar its entry.

»We went for a pivot in our short-term strategy and the first product we wanted to develop because we were able to utilise this synthetic peptide approach to, essentially in a matter of hours, model and predict how a small fragment of the virus could be printed out synthetically to serve as an active block of viral entry while also doubling as an immunomodulatory agency that's almost like a vaccine in the sense that it binds to neutralizing antibodies,« Watson says.

»That means that you could couple this sort of antidote with an expected prophylactic action and an expected immunomodulatory action. And so, we're commercializing what we are calling a prophylactic and therapeutic or, quote-unquote, an "antidote vaccine" that we're aiming to bring to market through the therapeutic pathway with the FDA,« Watson adds.

Ligandal History

The preliminary work for Ligandal's delivery system began back in 2011 when Watson was an undergraduate student at Rochester Polytechnic Institute.

He started to work in a laboratory that was building a nanoparticle-based delivery system for TALENS, which were a prominent gene-editing tool before CRISPR. After graduation, Watson moved to Silicon Valley and raised money to continue work on the delivery system.

The company initially struggled to convince investors because CRISPR, neurological gene editing, and the use of nanoparticles to do so were all simultaneously nascent fields of research, and many felt Ligandal's pitch was a long shot.

The company raised $2 million in 2017, which allowed Watson and his team to develop synthetic peptides that can attach to specific receptors on different cell types, forming the basis of the company's targeted delivery system for gene editing machinery.

But when the COVID-19 pandemic began, Ligandal rapidly pivoted and developed SARS-BLOCK, which Watson hopes will hit the shelves as a prophylactic therapeutic to block coronavirus infections.

Room-temperature-stable nasal spray

Pivoting from gene-editing to SARS-BLOCK took all of five hours, Watson explains, because the underlying system is fairly similar. He and his team had already done the leg work of developing a computational screening platform that could model how synthetic peptides would fold and bind to different cell types or receptors. So rather than starting from scratch, developing an experimental coronavirus therapeutic was essentially no different from merely adding another application to the existing platform.

There's still a long way to go before anyone might take SARS-BLOCK to prevent or block a coronavirus infection. Since August, Ligandal has been speaking to federal agencies in the United States like the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) and pharmaceutical companies that would be able to help mass-produce and distribute the product.

»Over the next several months, we'll be working with them as well as contractors to perform the preclinical studies that we need to complete to be able to file an emergency investigational new drug application with the FDA, and take it into a Phase I. Ideally, a combined Phase I/II study that measures both the safety and efficacy of the compound in reducing the severity of infection,« Watson says.

Watson envisions an over-the-counter, room-temperature-stable nasal spray that could be taken before and even after potential exposure to the coronavirus. SARS-BLOCK, if upcoming preclinical and clinical trials go well, is expected to help the body better recognize and fight the coronavirus by stripping away its means to hide from an infected person's immune system, Watson explains. That way, it could be taken alongside or independently of the FDA-approved vaccines to protect people in a conceptually-similar fashion.

»Right now, only one per cent of the United States is vaccinated,« Watson says.

»And even as we proceed in vaccinating a larger percentage of the population, the notion of approaching herd immunity is going to be very difficult, even accounting for vaccines covering some of the new strains. So, we see this as an adjuvant therapeutic, if you will. We would like to see it enhance the vaccine response. And we'd also like to see it act as a freestanding therapeutic that can bolster people's response and resilience to the virus, regardless of their vaccine stance,« Watson adds.

Long-term vision targeting all tissues and cells

Meanwhile, work on Watson's original vision — a universal gene-editing delivery platform — continues, even if fighting the pandemic has become his main priority.

Down the road, Watson hopes to expand on the foundational groundwork he's done on targeting and binding to cells in the nervous and immunological systems — which are of particular interest to researchers developing new gene therapies — and finally be able to develop a targeting ligand for any known or unknown cell type based on its specific receptors and markers.

»We want to replace the need for having an antibody with being able to make small synthetic peptides that can predictably target different cellular receptors. The scope of that is nearly limitless. Of course, you have specific questions about biodistribution and tissue and organ penetrance when you're developing different nanotherapeutics. That has to be taken into consideration,« Watson says.

»Our long-term vision is for everything ranging from regenerative medicine and ageing if you will, and senescent therapies down the line to, more immediately, some of the more accessible tissues and cell types for a lot of rare diseases and cancers. And extending beyond that to additional systemic organ targets. So that's perhaps a five to 10-year vision,« he adds.

SARS-BLOCK: Not Another Antibody Cocktail

The biggest misconception about SARS-BLOCK, Watson says, is that people mistakenly assume it's a monoclonal antibody cocktail like the one developed by Regeneron.

Rather, SARS-BLOCK is an immunomodulatory prophylactic, more like a vaccine than an antibody cocktail, but one that can theoretically be administered even after exposure to the coronavirus. SARS-BLOCK strips SARS-CoV-2 of what Watson called its 'invisibility cloak' — it keeps the coronavirus from blanketing itself with the bloodstream's free-floating ACE2 that typically makes it harder for the immune system to spot it.

That allows for a stronger immune response, Watson says, without the frequent re-exposures that might cause a more severe infection down the line.

If all goes to plan, Watson hopes that Ligandal's platform will help standardise what he calls the 'piecemeal' gene-editing field.

»You'll see a bunch of people targeting the liver, or a neurological company, or a company that defines three targets. And so there is a need and we hope to fill that need by creating the broader, more cohesive systems that all these companies can use,« Watson says.

»And that's our goal: To collaborate with as many of these companies as possible and to see this technology really come to fruition, being applied to an entire ecosystem rather than just one company commercialising everything,« he adds.

Dan Robitzski is a science journalist and former neuroscientist based in Los Angeles.

Tags

CLINICAL TRIALS

Sponsors:

Base Therapeutics (Shanghai) Co., Ltd.

Sponsors:

Base Therapeutics (Shanghai) Co., Ltd.