The Future of CRISPR, As Kevin Davies Sees It

CMN Intelligence - The World’s Most Comprehensive Intelligence Platform for CRISPR-Genomic Medicine and Gene-Editing Clinical Development

Providing market intelligence, data infrastructure, analytics, and reporting services for the global gene-editing sector. Read more...

CRISPR's potential to improve human medicine is nearly unfathomable, but there's a long way to go before it gets there - and many unresolved ethical issues along the path.

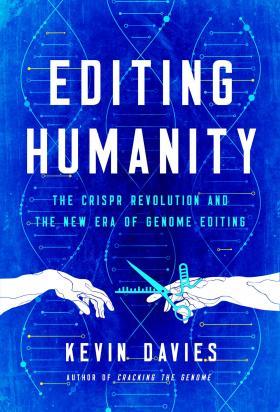

Kevin Davies is Executive Editor of The CRISPR Journal, which is dedicated to the science and applications of gene editing. He also recently published his latest book, »Editing Humanity: The CRISPR Revolution and the New Era of Genome Editing« which tells the story of the sung and unsung heroes of the story of CRISPR.

We caught up with Kevin Davies to learn more about the issues facing the field of CRISPR research and where it's all headed.

Because we spoke for nearly an hour, the following conversation has been abridged for length and clarity.

-Hi Dr. Davies, thanks for taking the time to chat today! Now, you have a storied career in academic publishing, to speak nothing of your books. I'd love to learn a little bit more about your trajectory — I notice that your role in publishing gradually became more specific from Nature to Nature Genetics to now the CRISPR Journal. Was CRISPR always your specific interest, or did you find yourself following the field as it grew?

I wouldn't quite say it got more specific because when we pitched The CRISPR journal, I viewed it as a very multidisciplinary journal. If you think of the subjects that are fair game within a journal serving the CRISPR gene editing community, it's microbiology, it's cell biology, it's virology, it's human genetics, it's medicine, it's bioethics, it's evolution, it's gene drives, you know, it's an extraordinarily wide array of topics.

And so for the Mary Ann Liebert publishing company [publisher of The CRISPR Journal], it was a very different beast. When you have a publishing company like that that publishes 80 or 90 journals, you will usually launch a journal and find a little niche that you feel is underserved. If you think of a cake, or a pie chart, it's a bit like it's another slice of the cake. And I said to them »No, The CRISPR Journal, we're the buttercream filling, we go everywhere,« because this tool is going to be used in so many different fields.

I just think this field has way is too much momentum, it's too exciting. And if someone's going to cover it, it may as well be us. And they loved that idea. So, by the spring of 2017, I was launching The CRISPR Journal and writing a CRISPR book.

-So it wasn't always the end goal, it was more that the field was ready for that primetime attention?

Exactly. When I write a book, it's a very simple recipe, it has to be about genetics, because that's really the only thing that I think I know anything about. It has to be a genetic story that I think has broad impact and interest to the general public. The discovery of the breast cancer gene, the sequencing of the human genome, and the dawn of consumer genetics - you can see whether I pulled those off or not, but those stories all had larger-than-life impacts on society and the general public. And the third element is that there has to be some human interests; there have to be some gripping characters that you can build a narrative around. And of course, with CRISPR, that soon became apparent.

The Holy Grail of medicine

-Oh, absolutely. To move on from the history, one of the things I'm interested in learning from you, as someone who has followed and been involved in so much of this space, is where it's all going. It seems that discussions about CRISPR hint to there being a natural end point to the field, sort of an ultimate goal. For instance, you hear about progress toward these things like so-called designer babies. Of course, that's not how any scientific field works, but the tools geneticists work with do get more refined and more powerful. To that extent, where do you see the field heading, as someone who follows much of the research published on CRISPR?

So the idea, simply put that a new technology like CRISPR or its new iterations like base editing can modulate as little as a single letter of the genetic code and repair a broken gene and restore health to a patient with a genetic disease, I mean, that's close to the Holy Grail.

If you're a geneticist or a clinician, it doesn't get much better than that.

“If you're a geneticist or a clinician, it doesn't get much better than that - Kevin Davies”

-But is there some sort of unrealised goal that scientists are focused on, like sequencing the human genome once was? While I'm sure it doesn't exist, is there anything approximating a finish line?

I think the most gratifying part of the story is that while writing and closing the book, we started to hear about patients like Victoria Gray, the sickle cell patient from Mississippi, who is the first American patient to be treated in the CRISPR Therapeutics gene-editing trial, and by all accounts after a year is doing incredibly well. Nobody wants to use the c-word »cure« yet, but all the results looked great.

Now, we've also got to extend that trial to dozens, if not hundreds of additional patients. And, I think, keep our hopes and expectations firmly grounded and not get ahead of ourselves. But that's amazingly exciting.

-I'm glad you mentioned the Holy Grail aspect of it before, because that's one of the things I planned on asking about. In your book, you wrote that CRISPR is the closest thing scientists have to »the coveted chalice of salvation.« That's particularly evocative, but it also suggests you think that there's yet-untapped potential for the technology. Where do you feel that potential lies? For instance, are there unexplored or nascent applications for CRISPR from a medical standpoint? Are there things people have tried but not quite sorted out?

Yeah. We're just starting to see a new wave of CRISPR gene-editing companies. Everyone's familiar with the big ones: CRISPR Therapeutics, Editas, having been joined by Beam Therapeutics. So you have these publicly traded CRISPR or CRISPR-derived companies. And now there's a whole wave of new companies that I didn't talk about much in the book, because I mean, some of them are just coming out of stealth mode now.

-Oh yeah.

And so all of these groups are finding new tools, new tools in the toolbox, or new strategies, and it's very exciting. And I think, whether it ends up that CRISPR-Cas9 becomes the predominant gene-editing method, or if it's base editing or prime editing or something that hasn't even been published yet, it's hard not to get excited by the thought that we're going to be able to perform, as David Lewis says, chemistry on the genome.

Base editing can, to a large degree, already do this. That doesn't mean it's going to be successful in the clinic. A lot of things still have to be figured out. But once you can do that, then the main question - and this is the consensus of the experts in the field, not me - is delivery. We've got the tools to do the chemistry and we can probably do it safely and precisely and transiently. But how do we get the components to the right cells, without triggering immune complications or other unwanted side effects?

So that's perhaps where there needs to be more attention paid. But I think once that is solved, then there's a catalogue called Mendelian Inheritance In Man that lists 6- or 7,000 known genetic disorders. So, what's to stop us now just poring through that book of genetic diseases and starting to check off more and more of them? Because once you can figure out how to target one liver disease, then there's hundreds more that, potentially with tweaks on that procedure, could become amenable.

-Right, and from following the space, it sounds like a lot of the challenge is in going from basic to applied science, if I can overly simplify it. For instance, there are possible treatments for neurodevelopmental disorders but it's difficult to penetrate more than five percent or some equally-dismal number of neurons. Is that really the main challenge? Actually, getting the sophisticated tools where they need to go?

I think it's a good example of how the ingenuity of the scientific community is going to now get this amazing toolbox. I think that for CRISPR gene editing - the world is its oyster, and there's so many applications that people are going to find for it.

-But to that point, getting this amazing tool where it needs to go is the obstacle. Is that the main issue across the board?

Yeah, I think so. We did an episode of our program, GEN Live. Neville Sanjana, neuroscientist at NYU Langone Health, said «delivery, delivery, delivery.» So that I think is the big challenge for therapeutic purposes.

Ethical issues on hereditary editing

-One of the other sides of this that I'd love to get your thoughts on is that - as inevitably happens with just about any new science, any emerging technology - there's a whole bunch of unfounded hype surrounding CRISPR. I'm curious if there's any aspect of the CRISPR or gene-editing field that you find particularly susceptible to that, and if that's a frustration that you've dealt with. For instance, designer babies or super-smart children?

No, really. I think one area that I almost purposefully sidelined in the book is the whole issue of biohacking. I just find it a little unpalatable. And I think I subconsciously decided that I didn't really want to give it a whole lot of airtime. But besides that, whatever area explored there are vigorous debates going on. Gene drives are a good example. The moment these are mentioned with a view to eradicating malaria, for example, you have the proponents who say there's half a million kids born with malaria each year, don't we want to save them? What else is working?

And then you have NGOs other activists in Africa who just see this as another example of Western colonial aggression and suppression and experimentation. They're so suspicious. Even though I think people's intentions are very, very good, they don't want anything to do with it. So that's not hype, exactly. But there are areas of controversy.

What I certainly tried to do in the book is play down this issue of designer babies. I think we learned a lot from the He Jiankui or HK scandal of 2018. Of course, as the book was being published, the National Academy of Science report on Heritable Human Genome Editing (HHGE) was being published. Very good report, I think it was well received on the whole. Our journal, The CRISPR Journal,published a fascinating commentary in which I invited 50 experts to respond - to just give us 200 words on what they thought about the report. We got responses from 36 people, including Doudna, Church, and many of the leading figures in the CRISPR world. Bioethicists, lawyers. It's an absolutely fascinating document.

-Could you lay out what the National Academy said in it? What was the response?

What the report has done is lay out a very narrow pathway for the potential clinical use of heritable genome editing. And few people, I think, would argue with the criteria that they've laid down. But really, if those recommendations stand, then we're basically saying: »We might condone, once we know it's truly safe, the use of heritable genome editing.« In cases where both members of a couple have sickle cell disease, for example. So they have two copies of the recessive gene by definition, so preimplantation isn't available for them to select a healthy embryo. So the only way they could have a biological child is to perform some form of gene editing to correct at least one of the alleles in the resulting IVF embryo. Those seem like extreme measures. But if you're that couple, and you want to have a biological child and medicine can give you that opportunity, I don't think society is in a position to say: »Sorry, no, we decided you can't do that.«

It's a very narrow roadmap. But let's take a longer-term view, what if, in ten, 20, 30, 40, 50 years, what if, for example, somebody was able to propose a gene-editing strategy that would abolish the presence of APOE4 - the high risk for Alzheimer's disease variant of the APOE gene on chromosome 19? If we could squash that in the embryo, is that something that would be worthwhile? If we could do that safely and reduce the incidence of Alzheimer's disease, particularly if your family had a known high risk, and you knew that you were carrying these E4 alleles? Because there is no drug available for Alzheimer's right now. It's a tough nut to crack. So yeah, do we want to think maybe down the road about offering hereditary gene editing for a situation like that? I'm not saying we should. But clearly, there are other questions that future generations will grapple with. That's a far cry from designer babies; I don't think anyone is really seriously suggesting that we're going to be able to tweak a few genes on the genetic rheostat. And suddenly, you know, notch you up five IQ points or something. That's crazy talk. So I tried to really squash those ideas in the book.

Public conversation needed before the next He Jiankui

-It's interesting that you present that thought experiment and talk about that narrow roadmap to human clinical relevance. You mentioned organisations deciding yes or no on various applications, which leads me to one of my questions: By whom do you think CRISPR ought to be controlled? Who ought to make these decisions about how it can be used? These are difficult questions about humanity and science that we're talking about?

There was a recent study in Science that said there needed to be much more public conversation and input about this. And I think even the co-chairs of the National Academy commission that we were just talking about would agree with that too. To be fair to the members of that commission, their brief was really to just look at the medical, scientific and technical questions. The ethics and societal questions have been punted to the World Health Organization. They have another committee that should report if not this year, then early next year. But I worry that for all their good intentions, that's just 16 people. Experts of differing degrees and geographies and backgrounds sitting in a room and taking testimony from different experts and coming up with a report.

But who's to say that's going to be the last word? People are going to poke holes in that just as they have in in every other report on this subject that has been published. And I think we're up to a couple of hundred now. So I don't think anyone's really exactly cracked how this is going to proceed. The National Academy report basically says this is a question that each country is going to have to weigh separately. Ultimately, it's a sort of a national responsibility. But there needs to be input from scientific experts, and other experts. And I think few would argue with the idea that gene editing can give some of these couples that we were just talking about a healthy biological child that is spared a disease like sickle cell or cystic fibrosis.

But then if you stand back, that's an awful lot of scientific and medical and ethical brainpower that spent a year trying to research the question of »Should a handful of couples be able to have a biological child?« It almost seems a little bit imbalanced, which is why I don't think that's going to be the last word. And I think, who should rein this in? It's tricky. The committee suggested that there should be some sort of international scientific advisory panel.

“10 years from now, who's going to stop someone else from taking matters into their own hands and setting up an offshore clinic? - Kevin Davies”

The worry is that when the dust settles on the [He Jiankui] debacle, when it's five or 10 years from now, who's going to stop someone else from taking matters into their own hands and setting up an offshore clinic somewhere and saying, »You know, I don't care what the rest of the setting what the experts say, I don't care what the Western society says. I know what my community wants, and I know what's best for my clients and my patients, and you're not going to stop me.« So I think my biggest concern is that we may not have seen the last of these efforts to just go it alone.

-I would love to zoom out from this one particular issue. Certainly He Jiankui's experiments are the most prominent ethical conundrum for the CRISPR community, but one of the things I was really curious about getting your perspective on is the broader concerns of bioethicists. You've said in the past that you've felt perhaps that bioethics gets overlooked in the CRISPR field. What are some of these issues that you feel have gone unaddressed?

It struck me as bizarre that at the American Society of Human Genetics in 2019, I think it was - I was appalled, because here's the first big international gathering of geneticists, since the [He Jiankui] saga. And it didn't get a single mention in the presidential address. I thought that was absolutely extraordinary.

-Was the attitude more »business as usual«?

I think there was one or two satellite, specialised discussions, you know, over in a back room somewhere. But I was just struck that here, for the first time, somebody has tried to interfere with the natural order of DNA sequences in human embryos and play God - whether you like that term or not - and that didn't merit some sort of condemnation from the President.

Of course, the final ethical question is what about the children? What about the three gene-edited children who were born, two in November 2018, one six months later? We know next to nothing about them and I think a lot of people would like to help them. We know the editing of the first two was so slipshod, people would really love to volunteer their time to give these kids the medical checkups and healthcare that they need. They may well be getting it; I have no idea.

-But that's the question.

That is the big question, yeah.

-And wouldn't you want to know what the genetic changes were? Not that these children should be subjected to study or anything, but the fact that so little information is available makes the whole case so much more nebulous.

Yeah. I'm not so interested in whether they are immune to HIV but I think the first thing is to ensure that nothing untoward happened to them, no off-target effects or the way that their CCR5 gene was screwed up hasn’t done some sort of harm. We sure hope not.

-Of course, of course. So we actually talked about everything I planned to ask you. But before I let you go, is there anything you want to add, whether it's about the book or the field in general?

It's the right question to ask at the end!

You know, the first quarter of the book is really devoted to the heroes of CRISPR. The heroes sung and unsung — and it's just a privilege to reflect and try to share some of these people's stories and the role that basic research played in getting this technology off the ground. So that's one message.

The role of serendipity always fascinates me. There's so many lucky breaks and twists of fate; publishing delays that have perhaps changed how history views the winners and the losers. It makes this an interesting story.

Dan Robitzski is a science journalist and former neuroscientist based in Los Angeles.

Tags

ArticleInterviewEthics in Genome editingOff-targetBase editorsCRISPR-Cas

CLINICAL TRIALS

Sponsors:

Base Therapeutics (Shanghai) Co., Ltd.

Sponsors:

Base Therapeutics (Shanghai) Co., Ltd.