First Chinese CRISPR gene therapy trial demonstrates safety

CMN Intelligence - The World’s Most Comprehensive Intelligence Platform for CRISPR-Genomic Medicine and Gene-Editing Clinical Development

Providing market intelligence, data infrastructure, analytics, and reporting services for the global gene-editing sector. Read more...

In 2016 a Chinese cancer patient was the first person in the world to be injected with CRISPR-Cas9 edited T cells. Now, there is a full publication in a high impact peer-reviewed journal on the same clinical study that involved 22 patients.

The data was published just two months after immunotherapy pioneer Carl June, at the University of Pennsylvania, US, first reported CRISPR gene-edited immune cells to be safe in humans.

»This study was similar to the one from my group, but they have a lot more patients here. We had three patients,« says Carl June.

»Both studies show that CRISPR works and without serious side effects. Which is good. Now we can build on these results, and we'll see advances.«

The Chinese patients all had aggressive lung cancer, and for these pioneers, the benefits were limited: only one of them is alive today and is now on a different treatment.

But to cure the disease was not the primary objective of the clinical trial, states co-leader of the new study professor Tony Mok, at the Chinese University of Hong Kong.

»To get this new CRISPR technology into the clinic we first need to ask if it is feasible and if we can do it safely,« says Tony Mok on a video call.

»Of course it is a bit disappointing that we don't see a miraculous treatment, but I think it is acceptable.«

He is keen to distance the research from the 'CRISPR-baby'-scandal in 2018 where the biophysicist He Jiankui used CRISPR to edit the DNA of human embryos that would become twin girls.

»The prior China event was very irresponsible, and we definitely do not want to go that route. We wanted a very well-governed clinical trial that demonstrates the feasibility and safety,« says Tony Mok.

So, there is no sensationalism here but this is a solid first step that has been vetted by the high standards of Nature Medicine.

»The major headline is a demonstration of safety, with no major toxicities reported. It sets the scene to expect more groundbreaking applications of these new techniques from China,« says professor Waseem Qasim, an expert of cell and gene therapy at the UCL Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health in the UK.

At the Center for Cancer Immune Therapy in Copenhagen, Denmark, professor Inge Marie Svane agrees.

»Both the US and the Chinese studies are about CRISPR editing of T cells in first-in-human studies, and are super important as first indications that the technology is safe in humans,« says Inge Marie Svane.

»To be tested in the clinic is very exciting and a big step for the technology, which has a huge therapeutic potential.«

CRISPR clinical trial in 2015

Tony Mok and first author Lu You of West China Hospital, Sichuan University in Chengdu of Sichuan Province in China are both lung cancer specialists.

Lung cancer is the most prevalent and fatal malignancy in China and worldwide, and there is no good cure.

With the university investing in the fast-developing CRISPR-Cas9 technology, they began to set up the clinical trial in 2015.

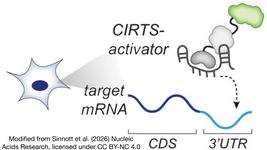

The strategy is to use CRISPR to disrupt a gene encoding the PD1 protein, so that PD1 is not expressed on the T cell surfaces. PD1 functions as a safety switch that cells can flip on to stop T cells from destroying them. Many cancer cells exploit this to evade the immune response.

Today the standard first-line treatment for lung cancer is immunotherapies that block PD1 using very expensive antibodies such as pembrolizumab. So the PD1 CRISPR gene editing strategy can be thought of as 'genetic immunotherapy' where you harvest T cells from a patient and remove PD1 before expanding the T cells and infusing them back into the patient.

As the first test of CRISPR in the clinic, it is an ideal strategy because it is much easier for CRISPR-Cas9 to cripple a single gene than to edit, add or replace a gene.

Safety and off-targets

From August 2016 to March 2018 a total of twenty-two patients were enrolled in the trial. All of these were very ill and had gone through several treatments prior, as is the norm for novel experimental therapies. Seventeen patients had sufficient numbers of edited T cells for infusion, but some withdrew because of disease progression and other reasons, so in the end, just 12 were able to receive treatment.

The researchers reported no serious side effects in any of the patients and found edited T cells in the blood in all patients four weeks after infusion.

In other words, CRISPR-Cas9 gene-edited T cells appears to be feasible and safe as a clinical application, at least for the short duration of this trial.

The main concern about CRISPR gene editing is off-target mutations. To study these, the researchers first used in silico methods to predict the 18 most likely off-target sites and sequenced the DNA in the T cells. They found a low frequency of mutations (0,05% on average) and concluded that this proved the treatment to be safe.

However, a reviewer disagreed.

»We got killed so many times by the reviewer,« laughs Tony Mok.

»How do you know it's these 18 and not 19 or 20?«

“Currently there is no consensus on how to look for off-target mutations, and I think the scientific community will have to agree on what is needed”

So to do a more thorough search they turned to whole genome sequencing »which is very expensive,« says Mok - of peripheral T cells they retrieved from the patients after infusion. Again, they saw only limited numbers of off-target mutations, and the reviewer was satisfied. But will whole genome sequencing be the standard in the future?

»Currently there is no consensus on how to look for off-target mutations, and I think the scientific community will have to agree on what is needed,« says Tony Mok.

»In the future, when you have tens and hundreds of patients, it would be difficult to do whole genome sequencing of all.«

In the future, the hope is that patients will live a long time after treatment and off-targets are going to be very important.

Modest outcomes for the patients

For these first patients, the outcomes were modest. The median progression-free period was 7.7 weeks, and median overall survival was 42.6 weeks. The best response was seen in a 55-year-old woman whose tumour mass initially shrank, and her disease remained stable for almost 75 weeks before finally progressing.

Conclusions cannot be drawn from just one 'interesting' patient. Still, in multiple biopsies, the researchers were able to see T cells infiltrating the tumour as a possible indirect demonstration of efficacy.

The efficacy is likely to improve in the future with better technology.

»I think there are so many things we can modify in the protocol to increase efficacy,« says Tony Mok.

One is the modest CRISPR editing efficiency which is due to the now outdated technology and would be improved by much more efficient technologies today.

Lu You suggest a combination therapy as a promising strategy.

»The tumour microenvironment of solid tumours is so complex. It is a significant challenge to overcome when using edited T cell monotherapy in the clinic. Thus, a combination of cell therapy with PD-1 inhibitors and even chemotherapy or radiotherapy should be a promising treatment strategy,« says Lu You.

Another point of improvement will be to enrol patients earlier after fewer previous treatments. Cancer treatments often leave patients with precious few T cells with which to kill the cancer.

»At the end of the day, it's the T cell that does the work, and we need healthy T cells,« says Tony Mok.

»So going forward one of the main lessons, I think, is that rather than pushing this therapy at the very late stage, we may move up the line a little bit, when the T cells are still in good shape.«

Carl June agrees.

»Now I think you could justify moving to earlier-stage patients, maybe even patients at presentation,« says Carl June.

»These studies will allow the regulatory authorities in China, Japan, Europe, and the U.S. to now say there are enough people treated that this is not like some Frankenstein. Now people can build on this and find ways to actually cure patients with lung cancer.«

One time only treatment in the future

Both Mok and June say that a new chapter is opening in the cancer immunotherapy field, combining the cutting-edge technologies of CRISPR gene editing and T cell therapy.

»I think it's for the whole oncology community to consider: gene-edited cellular therapy is one potential direction for the future. And I think it will be the next wave of treatment for lung cancer,« says Tony Mok.

It is not going to be tomorrow or next year, but in maybe 10 years according to Carl June, and the big potential benefit compared to current immunotherapies is that it could be a one time only treatment.

»That's the goal. Lu You's group, my group and others will have to show that cell therapy is better than antibody therapies,« says Carl June.

»We have done that in leukaemia. People were using antibodies, and now they don't because it works better to use cell therapy. But I think the lung cancer field is about 10 years behind where we are with leukaemia.«

Tags

CLINICAL TRIALS

Sponsors:

Base Therapeutics (Shanghai) Co., Ltd.

Sponsors:

Base Therapeutics (Shanghai) Co., Ltd.