PD-1 Targeted Cancer Immunotherapy Meets CRISPR

CMN Intelligence - The World’s Most Comprehensive Intelligence Platform for CRISPR-Genomic Medicine and Gene-Editing Clinical Development

Providing market intelligence, data infrastructure, analytics, and reporting services for the global gene-editing sector. Read more...

Özcan Met points through a window into the cleanroom where his team is preparing immune cells for the clinical treatment of cancer patients. A white device resembling a large toaster sits on a trolley opposite two flow benches. It is a bioreactor where the patients’ own cancer-fighting immune cells are expanded before being infused back into them. The process is part of a routine workflow to prepare for an established immunotherapy called adoptive T cell therapy (ACT) with expanded tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs).

Normally, the workflow takes about five weeks, but now an extra step has been introduced by the research team at the National Center for Cancer Immune Therapy at Herlev University Hospital in Copenhagen, Denmark. Here, CRISPR is used to release an inherent brake, the checkpoint inhibitor PD-1, in the immune cells and thereby improve their ability to fight cancer cells. The extra gene-editing step is seamlessly integrated into the ACT workflow, follows all clinical standards, and it only adds one hour to the whole five-week workflow. And Özcan Met is convinced that the small extra step will improve the outcome of immunotherapy and translate to a giant leap for patients.

“It is a hit-and-run strategy that takes very little time to prepare and perform, and it only allows the CRISPR reagents to work for a relatively short period before they are degraded in the cells. In this way, we can integrate the gene-editing step in a clinically meaningful, GMP-approved workflow and at the same time reduce the number of off-target effects”Özcan Met

TIL-based ACT and PD-1 ablation or blockade are both established types of cancer immunotherapy, and Özcan Met is not the first to combine them. But the trained biochemist and tumour immunologist believes that his distinct CRISPR delivery strategy has unique advantages. In a recent paper in Molecular Therapy: Oncolytics, his team reports using electroporation to deliver ribonucleoprotein complexes (RNPs) containing CRISPR-Cas9 protein and guide RNA (gRNA) to immune cells without using any vector, and this strategy comes with two significant benefits.

»It is a hit-and-run strategy that takes very little time to prepare and perform, and it only allows the CRISPR reagents to work for a relatively short period before they are degraded in the cells. In this way, we can integrate the gene-editing step in a clinically meaningful, GMP-approved workflow and at the same time reduce the number of off-target effects,« Özcan Met explains.

PD-1 in Immunotherapy

Programmed cell death 1 receptor (PD-1) and its ligand programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1) are immune checkpoint proteins found on the cell surface of T cells. Under physiological conditions their interaction results in T cell immune suppression, but cancer cells can hijack this pathway to escape immune detection. However, this can be reversed by blocking PD-1’s interaction with PD-L1. This has resulted in an intense research effort to investigate the underlying mechanisms and the clinical utility of inhibitors targeting these checkpoint proteins as therapeutic anticancer drugs. From British Journal of Cancer

Clinical trials could start already next year

Michael Mitchell, an expert in the delivery of nucleic acids for cancer therapy, agrees. He is a Skirkanich Assistant Professor of Innovation at the Department of Bioengineering, University of Pennsylvania and did not participate in the study. He says:

»Gene editing of T cells remains challenging because the RNP, also known as the gene-editing complex, is not readily taken up by T cells. Electroporation is an excellent choice for RNP delivery because it provides a direct pathway of entry into T cells to enable gene editing.«

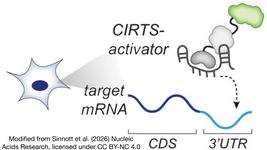

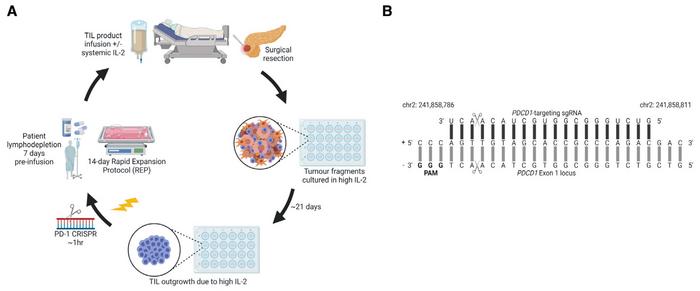

About 21 days after surgical resection of tumour fragments from patients, CRISPR was performed on TILs that had grown out because of high IL-2 in the culture medium (Figure 1). Edited cells were subsequently expanded to around 3,000-fold using a 14-day rapid expansion protocol (REP), and then they were - theoretically - ready for infusion into the same patient. This last step will, however, await approval for clinical trials. But that might not be far away, says Özcan Met:

»We are now preparing the investigational medicinal product dossier (IMPD) documentation for the Danish Medicines Agency. Since we don't introduce any vector sequences or viral components and only make a very small adjustment to a clinically approved workflow, we believe that from a regulatory perspective this new procedure is not crucially different from what we normally do. So, we plan to initiate and complete a pilot study with CRISPR edited TILs in metastatic melanoma patients already in 2023.«

PD-1 is efficiently knocked out

The gene-editing approach was to knock out the PD-1 encoding gene, PDCD1, using a gRNA that targets a locus in exon 1. gRNA was mixed with HiFi Cas9 nuclease (a high-fidelity R691A mutant) and a commercial electroporation enhancer to obtain RNPs that were immediately used for electroporation of TILs. Cells were handled gently and rapidly, and the whole procedure resulted in a TIL recovery rate of 79%. This was only slightly less than mock controls electroporated with a commercial negative control gRNA. Edited and mock samples expanded to the same level and the calculated CD4/CD8 ratios at day 14 were comparable. These results indicated that PD-1-targeted CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing is compatible with a TIL-based ACT workflow.

Analyses of gene-editing outcomes indicated 87% indel formation in the targeted area, with the vast majority of these being frameshift indels. Further analysis revealed that 58% of indels were either -1bp or -16bp and to a lesser extent +1bp. Determination of potential off-target sites with up to four mismatches revealed only one potential off-target site, but Indel Detection by Amplicon Analysis (IDAA) of this site concluded that no off-target editing had taken place in any edited samples.

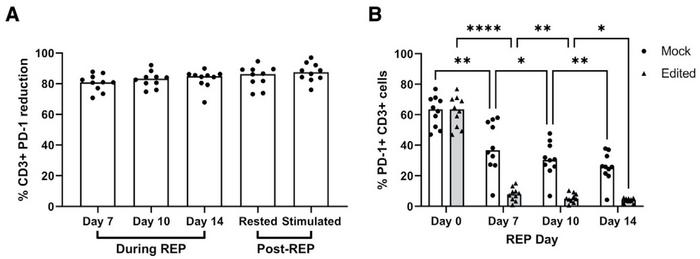

The high gene-editing performance was backed up by analyses of the effect of PDCD1-targeted CRISPR gene editing (Figure 2). Flow cytometry revealed over 80% reduction in the surface expression of PD-1 on CD3+ TILs compared to mock controls after seven days. The proportion of cells expressing PD-1 was also substantially lower in edited compared to mock samples. Moreover, a strong positive correlation was observed between indel percentage and surface PD-1 reduction after 14 days.

The functional effect of gene editing is hard to test in vitro

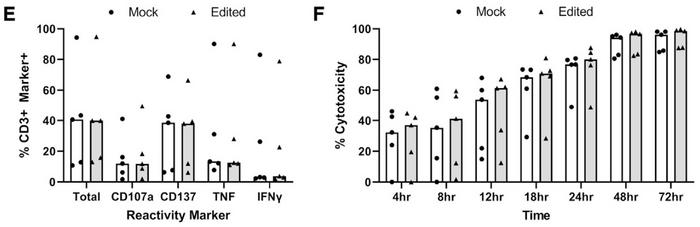

The functionality and phenotype of expanded PD-1-edited TILs were analysed in several ways and compared to mock cells. Flow analysis of contextually relevant cell surface and intracellular markers revealed few differences between edited and mock control samples, and no differential expression of any of 2,922 quantified proteins was observed. Moreover, upregulation of reactivity markers and cytotoxicity after co-culture with PD-L1 expressing autologous tumour cell lines followed the same pattern in edited and mock TILs (Figure 3).

Christian Blank from the Netherlands Cancer Institute is a pioneer in immune checkpoint inhibition. He was not involved in the study but has read the paper and studied the results.

»The effect is very strong on PD-1 expression, but I do not see a lot of effect on the function. So, this technique might become more relevant for T cell receptor transgenic T cells,« he says and points to another immunotherapy strategy in which T cells are engineered to express artificial receptors targeting tumour cells.

“As a minimum, we expect our gene-edited cells to perform as good as standard TIL-based ACT. When we move into the clinic, however, I’m convinced that they will perform better, but we just don’t know how much better yet”Özcan Met

But Özcan Met is more optimistic, and he is convinced that clinical trials of PD-1 gene-edited TILs will show improved performance in clinical trials.

»It is difficult to measure the effect of PD-1 knockout on the ability of T cells to kill cancer cells in vitro, because you also need antigen-presenting cells to activate the PD-1/PD-L1 axis. Our experiments show that CRISPR editing of PD-1 does not have any negative effects on the ability of TILs to express important surface proteins and to recognise tumour cells. So as a minimum, we expect our gene-edited cells to perform as good as standard TIL-based ACT. When we move into the clinic, however, I’m convinced that they will perform better, but we just don’t know how much better yet,« explains Özcan Met.

Michael Mitchell shares the positive outlook and says:

»Overall, the study is very exciting because it now applies gene-editing technologies towards tumour-infiltrating lymphocyte-based adoptive T cell therapy, with the potential to induce durable responses in a range of cancer types.«

Link to the original article in Molecular Therapy: Oncolytics:

To get more of the CRISPR Medicine News delivered to your inbox, sign up to the free weekly CMN Newsletter here.

Tags

ArticleInterviewNewsin vivoNon-viralElectroporationRibonucleoprotein (RNP)CancerAdoptive T cell therapy (ACT)ImmunotherapyTumour-infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL)Cas9

CLINICAL TRIALS

Sponsors:

Base Therapeutics (Shanghai) Co., Ltd.

Sponsors:

Base Therapeutics (Shanghai) Co., Ltd.